A different edit of this story appeared in The Cary News and The News & Observer in January 2013. I had first heard of Michael Mendy’s case a year earlier, through his obituary, when the reasons for his death still were unclear. In the months afterward, his doctors and his mother realized the awful rarity of his case, and they eventually shared this story with me.

It wasn’t bacteria or a virus that took Michael Mendy’s athleticism. It wasn’t an inherited illness that put him in a wheelchair with a feeding tube. No toxic substance was in his blood, stealing his speech.

At age 13, Michael suffered a spontaneous ravaging of the brain. It came on like old age, with no external cause or explanation, decades before it should have. The odds of a death like his, at age 16, are perhaps one in 600 million.

The doctors say it was stochastic: Totally random. But his mother couldn’t have known that.

“I had to figure it out. I had to find an answer. I had to find a doctor that could help him,” said Kathleen Mendy. “You don’t think you’re going to come across something that nobody’s ever seen.”

The onset

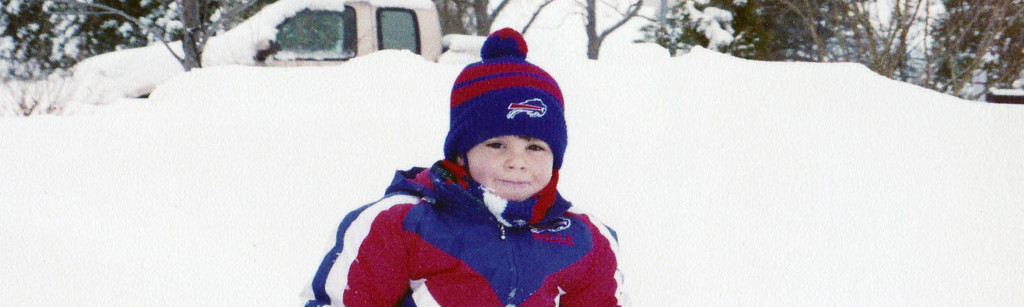

She thinks it started on Michael’s 13th birthday in 2009.

On that January day, another boy knocked Michael’s head to the court during a basketball game. He was playing again a minute later, his mother watching with a tinge of worry.

The symptoms of a years-long illness crept in that weekend, during Kathleen and her only child’s trip to Florida for the Super Bowl trip, Steelers versus Cardinals. That’s where she first saw Michael’s confusion, his unsure movements and his inexplicable crying.

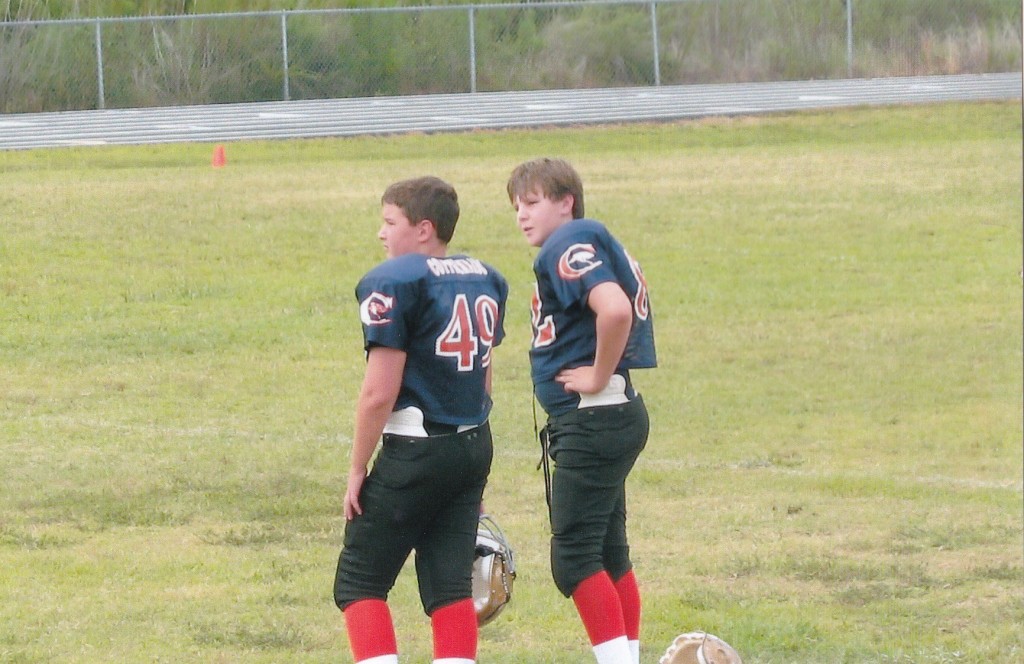

It seemed at first like the troubling wake of the teen’s second concussion in three months, but that theory would change. During the next three years, in a nightmare that kept unfolding, the brawny teenager would drop almost half his body weight, spend months in the hospital, lose his ability to speak and lie debilitated by simple infections.

The printed record of Michael’s hospital visits and test appointments is three and a half pages long. It documents an increasingly desperate search, listing 140 days in the hospital, 91 visits with doctors and 426 therapy appointments from 2009 to 2012.

“I always thought he would get better,” Kathleen Mendy said. “I used to always tell him, ‘Michael, one day you’re just going to run out of your bedroom, and you’re going to come running downstairs, and you’re going to be all better.’ ”

That turning point wouldn’t come. While his friends went on to high school, Michael was confined to a wheelchair and fed through a tube. His care grew so intense that his mother brought on a full-time medical aide.

Michael’s father, who is divorced from Kathleen Mendy, drove in from Florida each time his son entered the hospital, and Kathleen Mendy’s family often visited from New York.

Each treatment was more esoteric than the last. By the end of 2011, the Mendys had seen more than 30 doctors, medical specialists, faith healers and alternative practitioners.

“I tried chiropractors, reflexology, myofacial therapy,” Kathleen Mendy said. “I tried everything.”

‘I’m so glad I didn’t know’

The realization came to Kathleen Mendy on the last night of January 2012, the 22nd day that Michael spent in a UNC hospital bed.

He’d been kept alive in an intensive-care unit by a breathing machine since an infection took hold of his lungs. The mysterious disorder had left his body unable to respond.

The memory shakes Mendy to tears. The scene sticks in her mind.

“Not until the night before he died, is when, honestly, it hit me,” she recalled.

The doctors laid a choice before his parents that night. Michael could go home with a tracheotomy and a ventilator, but they believed he’d live just a few months longer. Or doctors could remove him from life support.

His parents didn’t want him to suffer anymore. On Feb. 1, 2012, doctors took Michael off his ventilator.

Only months later would Michael’s family learn the reason for his degradation and death. An autopsy showed the teenager had died of sporadic fatal insomnia, a subtype of Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease.

“I’m so glad I didn’t know what it was” before Michael died, Mendy said. “Because then I wouldn’t have had hope.”

‘Over and over’

“This disease is a descent into hell,” said Florence Kranitz, president of The Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease Foundation.

Kranitz saw her husband die in 2001 of an ailment similar to Michael’s. Since then, she has heard the stories of many of the 300 CJD victims her organization identifies each year, including cases of fatal insomnia.

“We get this phone call, and tragically it’s the same phone call over and over again,” Kranitz said. “They’ve never heard of this disease.”

The story she heard from Kathleen Mendy fit the profile, with one exception. Almost everyone afflicted by CJD subtypes is older than 45, except those who contract a variant of the disease genetically or through contaminated beef, which Michael had not.

Michael’s case quickly drew the attention of national experts, including Pierluigi Gambetti, director of the National Prion Disease Pathology Surveillance Center in Ohio. Gambetti, a pioneering researcher, examined Michael’s brain and in April identified his disease as sporadic fatal insomnia.

Gambetti later would take hours to talk with Mendy about her son’s death. Sporadic fatal insomnia and CJD, he explained, are part of the still-mysterious field of neurodegenerative diseases, including Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s.

Some of these ravages of the brain, such as mad cow disease, begin with an infection from the outside. CJD also can be caused by an infection of a type of prion, or pathogenic protein, often transmitted during surgery.

Like a virus, a prion can essentially “breed.” The virus hijacks human cells, and the prion reshapes other proteins into its own mutated form. When a prion or virus propagates enough, it can destroy its host.

But there’s a crucial difference: The prion also can come from within. Gambetti said he believes Michael’s disease began when the boy’s brain misfolded a protein, creating a prion instead. The defect may then have multiplied out of control and ruined the body’s delicate balance.

It’s not uncommon for the body to make mistakes. Neurons and other cells normally catch and eliminate prions before they replicate. These defensive systems may grow weaker with age; some people may also inherit weaker defenses.

But Michael was a teenager, with no apparent family history of neurodegenerative diseases. Gambetti put the odds of such a case at 1 in 100 million in the general population; another doctor said it was 1 in 600 million.

In fact, Michael may be among the youngest to be affected by any neurodegenerative disease without an inherited or outside cause. “We just haven’t seen this disease affect someone this young,” said John Trojanowski, a professor of geriatric medicine at the University of Pennsylvania.

Gambetti, who played a key role in the discovery of fatal insomnia, theorizes Michael’s illness was random. It may be that, by chance or some unknown factor, Michael’s brain bred its own pathogen.

“The bodies of all animals are a marvel of things, in positive and negative,” Gambetti said. “They can do things striking for the good, but also for the bad.”

Looking to others

Nearly a year after Michael’s death, Kathleen Mendy finds love and support from family, friends and Compassionate Friends, a local support group. But the extreme rarity of Michael’s case is isolating.

When she attended a CJD conference last summer with her twin sister, they met the families of people who had died in middle and old age.

Some nights she goes up to his room. It’s lined with dozens of sports team caps and trophies. Athletes’ names are still painted on the blades of his ceiling fan, and the UNC comforter is still on his bed.

All that’s new is the shrine on the desk, where Michael’s photo stands near a glazed statue of praying hands.

“Sometimes I think I’m OK, and other times it’s like it just happened last night. It’s like a rollercoaster,” Mendy said.

She may have as many logical answers now as she’ll ever get – a medical, if not a spiritual description of why Michael died.

She still doesn’t know what it was that made her son vulnerable. She believes Michael’s concussions triggered his illness, but his doctors haven’t confirmed the idea.

“I’m a little bit resolved that I’ll never hear the answer,” she said. “It would be nice to know, but if I don’t know it, it’s not what matters now.”

She finds hope instead in the idea that she could help others; she’s thinking of writing a book and becoming a public advocate for those who suffer with CJD.

Meanwhile, as Michael’s birthday and the first anniversary of his death approach, Gambetti and one of Michael’s former doctors are preparing to present his case to their respective medical communities. As painful as the case is, “its rarity may contribute to expand the knowledge on this terrible disease,” said Gambetti.

He hopes his research one day will allow much earlier diagnosis and treatment of fatal insomnia. Such a breakthrough could key medical progress across the spectrum of prion-related diseases, which are fatal in practically all cases, he said.

Gambetti’s research into Michael’s case will soon yield a more immediate result, too: He’ll be able to tell caregivers that sporadic fatal insomnia can strike not just the mature, but perhaps those just beginning their lives.

And with Michael’s story spreading, the next stricken family may at least know the harrowing path ahead.